The Rise of Vocational Education and Training - 1970s

In the turbulent 1970s, technical education was finally given both the close attention it deserved and the means to progress further in implementing needed change with significantly increased funding. The decade also heralded significant developments in national curricula and the acronym TAFE entered the lexicon of Australian education.

The Kangan Report

In 1970, a report to the Commonwealth recommended a massive boost of government and employers’ money into trade and vocational education, even suggesting a levy on employers to provide some extra funding. The needed spending would also reduce nationally the period of an apprenticeship from five to three years, and increase the availability of skilled workers, something the economy needed at the time. The report was produced by a committee of six from the trade unions, employer groups and Department of Labor and National Service representatives, who studied training methods in Europe and Britain.

The report was released to the public by the then Minister for Labor and National Service, Mr. Snedden. He said that: ‘...it was abundantly clear that the Commonwealth would have to provide money to help revolutionise industrial training...if the essentials are not adopted I doubt if we can meet the economic challenges facing us over the next 10 or 20 years. The capacity of manufacturing industry to compete with other countries will be diminished and this will inevitably lower standards of living generally.’

Part of the problem seemed to be that employers in Australia were spending far less on training than their counterparts in Europe and USA. There was an expectation that it was all the government’s responsibility. Australia also seemed to be unusual among developed countries in not having a national coordination of training to ensure standardisation of qualifications and training quality.

The report recommended, among other things, improved training for teachers, and greater flexibility so that, for instance, high quality instructors could undertake teaching in the workplace. Minister Snedden was confident that all parties would ‘accept the report in principle.’

In 1973 the Whitlam Government set up the Kangan Committee, which led to the most significant report in the history of technical education in Australia. This report was so critical, that it is natural to speak of ‘after Kangan’, as involving a new way of looking at this education sector.

The Kangan report followed in the wake of former enquiries such as the Wright Report (1954) which identified many of the issues which needed to be addressed in vocational training, and the Martin Report (1964), which brought about the creation of colleges of advanced education and senior technical colleges.In many ways, the ideas that were freely discussed and advocated over the years finally had a focus in the deliberations of the Kangan Committee which released its report in 1975.

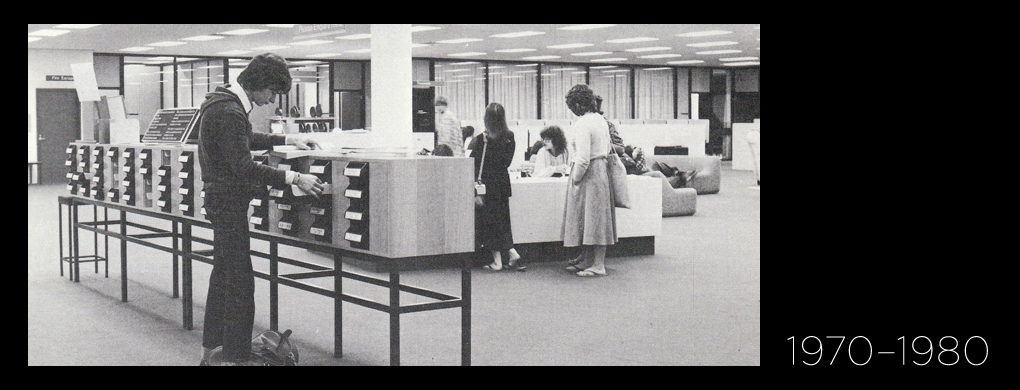

For the first time, we began to hear and use the terminology ‘technical and further education’ embodied in the acronym TAFE – part of the natural language of education today. Vocational education was seen as on the same level as other sectors, and the report sparked a dramatic growth in the technical/vocational sector. National curricula were first seriously developed in the 1970s, and this continued from that time on. The Commonwealth begun to directly fund the TAFE sector including providing direct subsidies to apprentices wherever they were employed. The Fraser Government continued to develop the vocational educational and training sector (VET), which came to be seen nationally as part of an expanding range of programs focused on creating opportunities for individuals to further develop themselves, and improve their chances of upward mobility in society.